Part 1 of 4.

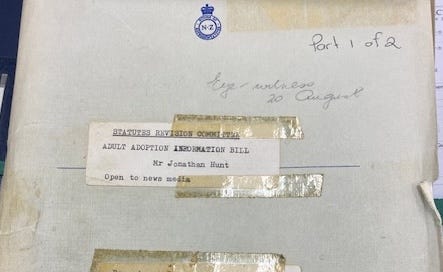

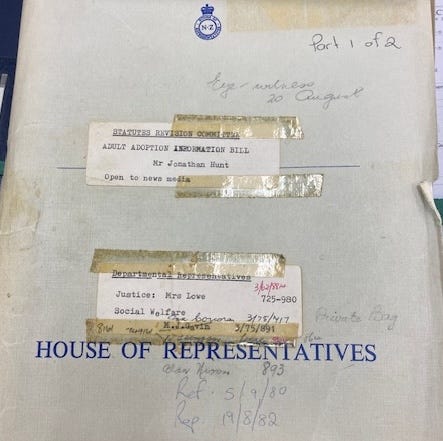

I heard about it on the radio. It was 1984 and an Adult Adoption Information Act (AAI Act) was being discussed at the highest levels. MP Jonathan Hunt described the effect of the 1955 Adoption Act on adults as cruel and unfair: “A child becomes a man or a woman and, as an adult, is entitled to perform any of the functions of society, whether or not he or she is adopted.”

Hansard provided more from Hunt:

Adoption involves two sets of people, usually only the birth mother … and the adoptive parents, … making a contract about a third party. When that third party becomes an adult, he or she has rights, and, in my view, those rights transcend the rights of the original contract.

It is 40 years since Hunt made that statement in Parliament.

The AAI Act (claimed to represent the beginning of open adoption despite having nothing to do with it) is officially described as providing greater access to information about origins.

It claims to balance the desires of adopted people, the rights of mothers, and the needs of adopters. Think about that for a moment:

In human hierarchy needs come first. They are non-negotiable; without them, survival and well-being are at risk.

Rights are next, they must be protected and upheld to ensure collective well-being.

That leaves desires - personal aspirations or wants that, while important, are secondary to needs and rights of others.

I cannot think of a more apposite description of the power structure in adoption.

The AAI Act was promoted as enlightened legislation. But, it turns out we were – in the words of Carl Sagan – ‘captured by the bamboozle.’

The singular promise of the Act: ‘greater access to information about origins’ in reality allowed for one thing only – your mother’s name.

Except it didn’t.

Mothers retain (still today) the right to veto their name.

As adopted people, we know that greater access to information is not the same as the right to all information relating to who we are and how we became adoptable.

The Act does not mention the copious records held on every adopted person (more on that in a future column).

The Act requires (still today) adopted people to be twenty years of age, despite eighteen being the legal age of adulthood for most activities. And to engage a counsellor. Even if you are a senior citizen.

You might think counselling is to assist the adopted person to navigate the profound, life-changing complexities of reunion. Instead mine was to ensure I understood my place.

It included being made to promise not to look for other family members or pursue or annoy those I might find. I was required to perform the role of a grateful adoptee. I had to show I was sufficiently respectful and that I was not in any way emotionally damaged by adoption.

I had to pretend I'd had a happy life. Only then did the counsellor agree to send me my original birth certificate, my founding document that she had access to and control over.

Except the document I received was not original. It was endorsed with a large red ILLEGITIMATE stamp.

The word original appears thirty-six times in the AAI Act.

A couple of years later, a new ‘original’ birth certificate arrived, the red branding replaced with a large black stamp. ‘Issued for the Purposes of the Adult Adoption Information Act.’

It included my adopted name, allotted to me only after the adoption order was finalised at nine months old. And the full biographical details of my adopters.

When asked why my supposedly ‘original’ birth certificate has been defaced in this way, the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) said: “The certificate is only for family history information and should not be used as evidence to support current identification purposes.”

They further described my original birth certificate as ‘essentially ornamental’. “Our Departmental Policy is to provide the endorsement on the pre-adoptive original birth certificate to ensure the record is not used to establish a new identity for the individual.”

Oh, the irony.

But surely any false use of a birth certificate is already covered under the Crimes Act?

A DIA staff member conceded I raised a fair point. He said they are treating the matter seriously: “I understand that this is a very personal matter for you, and I will endeavour to keep you up to date.”

He’s right. It is personal. However, it is also inappropriate to individualise systemic discrimination.

I then asked the DIA why a similar endorsement is not added to a post-adoptive ‘birth’ certificate:

It is a certainty that the endorsement is an internal policy and not a legislative requirement. Based on what we have been able to find out, it appears that it was an internal policy to add the endorsement in response to perceived risks that other agencies had that persons may create multiple identities. That is why we need to investigate the matter. And that risk could purely be around the integrity of agencies’ databases in that there should only be one record for one person.

One record for one person. Yes please.

But who are these agencies concerned that 100,000 plus adopted people cannot be trusted? And is there any other situation where a citizen must be regulated beyond the law to protect the integrity of government databases?

In further correspondence, the DIA said:

This anomaly is definitely relevant and important. As we discussed, I am meeting with my colleagues next week so we can investigate the issue. What we will be doing is establishing what the law says and making a recommendation to the Registrar-General. That may take several weeks.

That was the last I heard from him.

Months later, a principal advisor at the DIA acknowledged that an original birth certificate had once existed. She noted that, for a time, original birth certificates were issued without endorsements, but these were added due to the risk of fraudulent creation of dual identities:

The use of dual identities could occur when a person seeks to use two identities fraudulently by pretending they are two different people. Or where they have a criminal record or credit record under one name, using another name to try and evade the consequences of their actions.

Are they acknowledging that adopted people have two identities?

But seriously, do the adopted commit identity fraud at such a level that standard penalties alone are insufficient?

I ask for data on the number of adopted people charged and/or convicted under the Crimes Act for the fraudulent creation of dual identities:

I can confirm that the Department does not hold information on how many adopted people have been charged and/or convicted under the Crimes Act for the fraudulent creation of dual identities. This portion of your request must therefore be refused.

And in subsequent correspondence:

While the Crimes Act does provide some penalties against fraud, the Registrar-General has taken into account that penalties alone are frequently insufficient to prevent fraud. In practice, reducing the opportunity to commit fraud is also important. I have referred your comments to the Registrar-General as requested. He has considered them and determined that the current practice of including the endorsements should continue until such time that there is a change to the law.

So, no evidence of adopted people creating dual identities to commit crimes. But there is a crime here. And it has been overlooked at least 100,000 times.

Every person born in New Zealand has a birth certificate that states:

Any person who (1) falsifies any of the particulars on the certificate or (2) uses it, knowing it to be false, is liable to prosecution under the Crimes Act 1981.

The genetic strangers who record themselves as birth parents are openly falsifying the particulars on the certificate, and they go on to use that certificate knowing it to be false.

This crime is then forced onto every adopted person who must also use it, knowing it to be false.

In reality, all adopted people have four birth records:

· A birth printout, also known as a long-form or birth record. *

· An “essentially ornamental” endorsed original birth certificate.

· A post-adoption birth certificate described by the DIA as a “legal fiction.”

and

· And a true and correct birth certificate, identical to that held by every non-adopted citizen.

I want this last one: a singular record of my birth, with my real name, my mother’s name, and my father’s, proven by DNA*.

One record for one person. The person I was born as. The person I wish to die as. Why is that too much to ask?

The Adult Adoption Information Act is an entire Act of Parliament with a singular purpose that does not deliver on that purpose. If there’s humour in here somewhere, the joke is on us – the adopted.

There is so much more to unpack – part two next Wednesday.

Become a paid member for fully footnoted versions of this and all my columns.

Next up:

*Part 2/4 Your Very (Un)Original Birth Certificate.

Coming soon:

*DNA Be Damned: The impossible process of adding your father to your OBC.

I’m a late discovery adoptee and have spent much of my career working in government environments. The ‘false’ birth certificate was one of the things that I feel most aggrieved about. Especially the ‘expanded version’ that I had to pay for so I could prove my identity. That seemed ok at the time because I didn’t know I was adopted- but it felt like fraud once I knew it was fiction !

I was lucky to be given a free DNA test kit from a friend, which I used to find my birth father. Not that I got to meet him, as he died years ago. We still have no idea which brother my father is, but I have contact with that side of his whanau. I should never have been forced to go via a for profit genealogy company. I should have access to all information about my whakapapa. I also found that as a child of incest and family abuse, I was denied information held by child and family services. This information should have been given to me when I started my exploration about my adoption, especially as it would have helped support my ACC claim. I feel that there is a missed moment to expose the purported 'good' adoption was said to provide by not discussing the wider issues faced by people removed from their mother for the 'good' of the child. There will be 1000's upon 1000s of adults still living with the trauma of adoption, incest, and physical abuse. For those reasons, we should be allowed to gather all our information to help us gain access to help and support for our post trauma so that we can thrive.